The Building Blocks of Animation

Last week, we talked about how and why animation works in terms of cartoon representation; how simplified “iconic” images possess a unique ability to relate to the audience and amplify meaning. However, that discussion could be applied to any visual art – drawing, painting, sculpture, etc. Let’s move on to the unique properties of time-based media.

We know that animation is made up of deliberately composed frames, but how do those frames end up on the screen? There are currently three basic techniques used for “capturing” animation, with a few outliers and overlaps.

The first technique is frame-by-frame animation. In frame-by-frame animation, an animator creates each frame individually, in order. Hand-drawn or cel-based animation is a done frame-by-frame, as is stop-motion. Since each frame is being created individually, frame-rate is a major consideration for frame-by-frame work. Animation being done at 24 frames-per-second requires twice as many frames to be created as animation done at 12 frames-per-second.

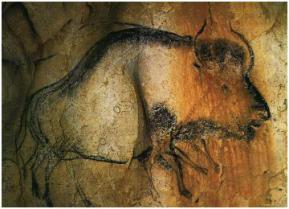

The most obvious examples of frame-by-frame animation are the “classic” animated films done before the advent of computer animation. However, frame-by-frame animation actually dates back to before the invention of film to simple toys like the zoetrope – and, possibly, to the dawn of art itself.

The most obvious examples of frame-by-frame animation are the “classic” animated films done before the advent of computer animation. However, frame-by-frame animation actually dates back to before the invention of film to simple toys like the zoetrope – and, possibly, to the dawn of art itself.

The second technique is keyframe animation, which is an evolution of the frame-by-frame technique. In keyframe animation, an animator defines the “key” moments in a sequence. When the project is computer-based, software then fills in the blanks. When the project is hand-drawn, the original animator goes back and fills in the blanks after the key poses are set, or hands the work off to another animator to fill in. The animators who fill in the blanks are called “in-betweeners” and they are essentially acting as human animation software.

Keyframe animation and frame-by-frame animation might seem distinct, but they are actually closely related and are often used within the same sequences. A traditional animator might start with keyframes, then fill in the in-between frames, then add additional details frame-by-frame. An animator using software for keyframe animation (like After Effects) might go through a similar process, beginning with broad keyframed movements, then tweaking individual frames one by one. Keyframing might seem like a huge time savings – and it can be! – but even when an animator is only setting the start and end points, there may be dozens of different actions happening in a sequence simultaneously. Three-dimensional computer-animated films (think Pixar and recent Disney animated films) are generally done using keyframes. One technique where keyframes can’t be used is stop-motion; because stop-motion animators are physically moving puppets, they can’t jump back and forth in a sequence to define keyframes.

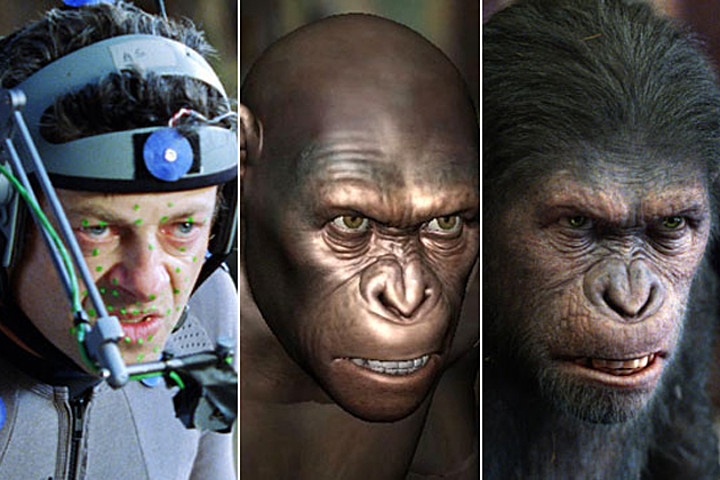

The third technique is motion capture. This is the newest animation technique and the one that requires the most specialized equipment and software. In motion capture, an actor wears a special suit (or make up, for facial motion capture) covered with reflective dots that can be tracked by software. As the actor moves, a camera interprets the movement of the dots and applies them to the movement of an animated character. Sometimes this is done after the fact and sometimes it is done instantaneously. It is now fairly common to see an actor in a motion capture suite on set interacting with actors in costume.

Because motion capture is created using “real world” movement, it can be used to create animation that is realistic and subtle. Motion capture is often used in the special effects industry, where believability is of the utmost importance. It is also commonly used to create animation for video games.

The biggest benefits of motion capture are speed, realism, and the ability to improvise. A motion capture actor can collaborate in the animation process – keyframe and frame-by-frame techniques rely solely on the animator. The downside of motion capture is that it can introduce too much realism – or, perhaps, the wrong kind of realism – into the animation process. When we watch something that we know is animated, we accept (and even anticipate) a certain level of exaggeration and a certain level of simplification. This relates back to our discussion of “iconic” imagery. Animation that looks nearly real, but seems just slightly “off” can be incredibly distracting. The industry term for this phenomenon is the “uncanny valley.” Animated films like The Polar Express have been criticized for looking too real to be cartoons and too cartoony to be real. The uncanny valley refers to this disconnect with regard to both visual representation and movement.

There are also some techniques that defy easy categorization. Marionette or puppet-based films are not truly animated, but they fit the definition of iconic cartoon representation. Rotoscoping, a technique wherein live-action photography is covered with cartoon art, falls somewhere motion capture and the other techniques. There are also still-image-based films (sometimes called “diaporamas”) that are composed of frames in sequence, but do not give the illusion of movement.

The 12 Principles

If the uncanny valley is a problem because we don’t expect animated things to move in a completely realistic way, how should animated objects move? What makes animation effective? The best guide probably comes from two former Disney animators named Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas in their book Illusion of Life. Johnston and Thomas defined twelve “basic principles” that animators should master. They are as follows:

- Squash and Stretch – The idea that the shape of objects and characters is flexible and determined by their movement. The classic example is of a rubber ball elongating as it falls and squishing down as it hits the ground.

- Anticipation – This is a small action that precedes a larger one, such as when you duck down slightly before jumping.

- Staging – This deals with the way a scene is arranged. Ideally, it should direct the viewer’s attention in a clear way.

- Straight Ahead Action andPose To Pose – Essentially, this is the difference between frame-by-frame (straight ahead) and keyframe (pose to pose) animation.

- Follow Through and Overlapping Action – These two techniques help animation seem more natural. In follow through, moving objects tend to keep moving past their destination because of inertia; for example, your arm keeps swinging after you throw a baseball. Overlapping action is the movement of multiple objects or body parts simultaneously, but at different rhythms or speeds.

- Slow In and Slow Out – Generally, objects in motion don’t move at a steady rate. Instead, they accelerate or decelerate depending on a number of factors. Slow in and slow out can tell the viewer a lot about an object’s weight, mass, and speed.

- Arc – Things very rarely move in perfectly straight lines – most action follows an arc trajectory. A thrown ball will move in a rounder or flatter arc depending on its speed. Walking is composed of small arcs from step to step.

- Secondary Action – This is a smaller action added by the animator to emphasize a bigger one. Things like facial expressions and hand gestures are often used as secondary actions.

- Timing – In its simplest terms, timing describes how long animated actions take to occur. Johnston and Thomas are specifically referring to the number of frames an action takes and how manipulating that number can change the meaning of that action.

- Exaggeration – The amount of exaggeration in animation is largely determined by the level of realism in the work. Often, exaggeration is used for comedic effect, but a certain level of exaggeration is usually expected.

- Solid Drawing – In two-dimensional animation, the animator should consider how the character or object would exist in three-dimensional space. This helps give things mass, weight, and balance. Without solid drawing, things tend to appear flat and floaty.

- Appeal – This relates to character design. Animated characters should be pleasing to look at. This doesn’t necessarily mean that they must by physically attractive, but they should be interesting to the eye. Exaggerating proportions and playing with shape is a good way to do this.

For an excellent and concise explanation of each of the twelve basic principles, check out Alan Becker’s series on YouTube.

Keep in mind that Johnston and Thomas’s principles are just that – guiding principles, not hard-and-fast rules. Squash and stretch or exaggeration can be used to varying degrees to make a piece more realistic or more cartoony. The principle of solid drawing could be ignored to make a piece deliberately surreal. Whether you follow the principles closely or purposely break them, the most important thing is that you understand and consider them as you move forward with your own animated projects.

Editing Animation

If you have any understanding of the production process, you know that the editor of a film has a tremendous role in shaping tone, pacing, and narrative. How does this apply to animation? While live-action films are generally cut from dozens (or hundreds) of hours of footage, the animation process doesn’t produce much, if any, “extra” footage. So what is the role of an editor?

As discussed in the following short documentary from The Royal Ocean Film Society, the editor on an animated project is actually a collaborator in the filmmaking process much earlier than a live-action editor is. Because animation is, by its very nature, tedious and time-consuming, you absolutely don’t want to waste time and money by creating shots that you aren’t going to use. On a live set, changing camera lenses, adjusting blocking, or trying something new with the lighting is relatively simple. When in doubt, you can film something multiple ways and then choose the best approach in post-production. Animators don’t usually have that luxury – they need to know the best approach before they start the animation process.

Even on short animated projects, planning is of the utmost importance. I generally start by writing a general outline, then some very crude sketches. From there, I draw more detailed storyboards, which I refine until I’m happy with the flow of the piece. Depending on the complexity of the sequence you’re working on, you may want to go a step further and create an animated version of your storyboards (known as an “animatic”). You should only begin animating once you have a clear plan and know that the shots will work together.

Assignment 2: Start Animating

For your first animation assignment, I’d like you to create something without the use of a computer. It can be done using stop-motion puppetry, paper cut-outs, collage, drawing on paper, drawing with chalk or a white board, or another “hands-on” technique. Create at least two seconds of animation at a minimum average of 12 frames-per-second (in other words, you must create at least 24 frames). Your animation should show an action and a reaction. Plan it out in advance and, as you work, keep the basic principles of animation in mind.

The easiest way to capture your animation is probably using your phone. There are a number of free apps for creating animation; I’d suggest Stop Motion Studio, which is available for both Android and iPhone. Stop Motion Studio allows you to take photos within the app and choose the frame rate at which they play back. If you’re starting with drawn images on paper, complete your artwork first, then take photos of the pages using the app.

One challenge is going to be keeping your phone steady as you work. You may want to consider securing your phone to a stable surface using rubber bands, tape, or clay. Even just leaning your phone up against something can help a lot. You will probably have to do some problem-solving and improvising to make things work – have fun and get creative!

Animating frame-by-frame like this is time-consuming and difficult to master. Don’t get discouraged! Seeing animation that you’ve created with your own hands come to life is incredibly rewarding. The goal here is to get a better understanding of things like motion, speed, and timing.

When your animation is finished, export the video and email it to me at dan014@bucknell.edu. If your file happens to be too big to email, drop it in your Google Drive storage and send me a link. Happy animating!